(Germany had by then absorbed the Sudetenland, annexed Bohemia and Moravia, and installed a collaborationist regime in Slovakia.) The men knew they were likely to die. In their 20s, they were picked from a small army of Czechoslovaks who had escaped to Britain in the hope of fighting to free their country.

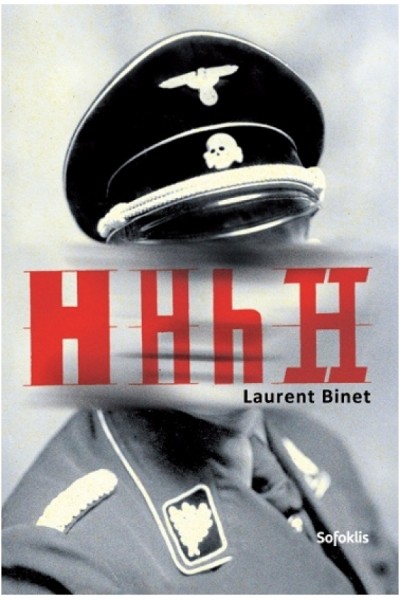

Still, Binet learns little about the early lives of Heydrich’s killers, Jozef Gabcik, a Slovak factory worker, and Jan Kubis, a Czech soldier. He recounts a conversation between Heydrich and his father, then reprimands himself: “There is nothing more artificial in a historical narrative than this kind of dialogue.” So he promises: “And just so there’s no confusion, all the dialogues I invent (there won’t be many) will be written like scenes from a play.” Amid myriad other digressions, he also finds time to opine on movies and books about the Nazis - and there is no denying he has done his homework. “His motto could be: Files! Files! Always more files!” Binet writes, adding nicely: “The Nazis love burning books, but not files.” In all, Binet concludes, “Heydrich is the perfect Nazi prototype: tall, blond, cruel, totally obedient and deadly efficient.”Įven as he writes, though, Binet (or the narrator) harbors doubts about his approach. As the head of the SS security service known as the SD, he showed a special gift for bureaucracy. To set the stage, Binet guides us through Heydrich’s early years - his musical talent, his brief naval career and his marriage to a Nazi sympathizer - to his rapid rise as a favorite of the SS chief Heinrich Himmler. This literary tour de force, now smoothly translated by Sam Taylor, earned Binet the Prix Goncourt du Premier Roman in 2010. And, in the end, his making of a historical novel brings a raw truth to an extraordinary act of resistance. We join him on his research trips to Prague we learn his reactions to documents, books and movies we hear him admit that he sometimes imagines what he cannot possibly know. By placing himself in the story, alongside Heydrich and his assassins, the narrator challenges the traditional way historical fiction is written. “I just hope that, however bright and blinding the veneer of fiction that covers this fabulous story,” he writes, “you will still be able to see through it to the historical reality that lies behind.” The best he can do, he concludes, is to provide a running commentary on the truth (or otherwise) of what he is writing. But now he decides it is dishonest to invent descriptions, dialogue, thoughts and feelings on a subject as serious as this. Like Laurent Binet, the book’s French author, he has spent years examining the murder of the SS general Reinhard Heydrich in Prague in 1942 with a view to retelling the story as a thriller. The nameless narrator of “HHhH” has serious misgivings about the novel he is writing.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)